“I am going back to the old house, where doors open whether I knock or not”

Sudanese poet, Mohamed El Hassan Salim Himeid

I write this as the chanting of demonstrations from neighbouring streets echo above the city of Khartoum. Just shy of five months after the June 3rd 2019 massacre dispersed the sit-in area, demonstrators have yet again taken to the streets of Khartoum to protest the lack of response to the killings. The sounds of the chant—freedom, peace, and justice!—drawing us all together. The ‘sit-in’ was an area occupied by protestors in Khartoum that was located across from the army headquarters; the location chosen by protestors to make clear their anti-military governing and call for change. The sit-in ran from the 11th of April 2019 until it was forcibly dispersed, in the early hours of the 3rd of June 2019, by use of deadly force from the Rapid Support Forces (RSF)—culminating in the killing of more than 700 individuals, in what is called the Khartoum Sit-in Massacre.

The collective feelings of anger and disappointment at the events of that day, at the fact that there is still no one being held accountable and no justice, leaves one wondering about how the boundaries of the sit-in area have simultaneously created boundaries where state terror managed to unfold. What makes the pursuit of well being, justice, and equity through political actions and audible demands by protestors constantly manifest a byproduct that inflicts pain on oneself? I mean, we know why but do we know how the built environment and its public spaces were implicated in processes of state terror? How can we channel inquiries that would enable us to survive the inevitability of state terror; to carry our concerns outside of the futile political dialogues saturating the aftermath of such devastation?

The Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) is one of the leading entities that aligned themselves with the demonstrations that sparked the revolution in Attbara (a northeastern region of Sudan) in 2018 and they began to guide and manage the demonstrations from then on. The SPA traces its roots to October 2016, when an alliance charter was drafted and approved by three of Sudan’s largest professional groups. Namely, The Central Committee of Sudanese Doctors, The Sudanese Journalists Network, and The Democratic Lawyers Association. The SPA is currently comprised of many bodies united under an agreed upon charter and common goals. As the 2019 demonstrations gained momentum, the SPA started to produce and distribute single-line urban plans that depicted public spaces and gathering points for demonstrators. Departing from the digital images of the plans published on Facebook by the SPA, the uprising has fore-fronted a radical standpoint on space, a perspective which deployed a politics of location from within public spaces in Khartoum.

We can ground the inquiry introduced in this text with a further focus on architecture, as one of the chief formalized tools of space making that creates the built environment in our world today and is a main reflector of the state’s imagination on people’s everyday reality. To answer these inquiries, it is helpful to think of ‘space’ as discursive and transformative, and thus rid ourselves of thinking of public space as something that remains static. In the case of the demonstrations in Khartoum, we will look at how the digital space intercepted some of the conventions of architectural language, namely ‘plans’, and how social media platforms directly influenced how the masses used, perceived, and ultimately mapped out alternative readings for the public spaces in Khartoum.

The built environment’s space discourses have had a lengthy attachment to immobility, physicality, and the direct monumentalizing of state ideologies. The idea that space is a ‘matter of fact’, and that space and place are merely vessels for human complexities and social relations, is terribly seductive. That which is “matter of fact ” not only anchors our feet to the ground, it seemingly standardizes and normalizes how we can move through and use built spaces, and that is something which is being translated in our space making practices. Thus, the physical environment is a materiality that holds and regulates; it hides humanity because it is “matter of fact” and because those inside of it, limited to the walls and spatial paradigms such as public/private, are often neither seeable nor liberated subjects. But the landscape, locations, and territories drawn out on this globe, our surroundings and our everyday places, the ‘containers’ of human violence, frequently disguise important patterns of social interaction and interdependencies that people have with the surrounding environment. They can hide what the Jamaican philosopher Sylvia Wynter calls “the imperative of a perspective of struggle.” Wynter’s perspective facilitates the focus on the ongoing struggles of the people of Sudan which have, since last year’s turmoil, culminated in the uprising.

The plans published by the SPA called on people to participate in the formation of demonstrations against the state and in turn, people called on the SPA to be a witness to what was happening on the ground. The demonstrations consequently progressed into an entire digital cultural practice that identified the spaces where people gather, and began the process of a collective re-visioning of their surroundings in order to get political demands across. People collectively devised and pursued survival hacks and uploaded stories and images to Facebook groups or their own timelines, reiterating actions that happened on the ground, and tagging the official SPA Facebook page. For example, posts often warned people of certain areas where snipers were stationed and they would also share tips on how to curb the effects of tear gas by urging people to carry vinegar in bags. The highlights that emerged from this process included the creation of fictional characters and animated personalities derived from the survival hacks introduced by people. One superhero character was named ‘bucket man’ and his super power was the deactivation of tear gas canisters by placing a bucket over them.

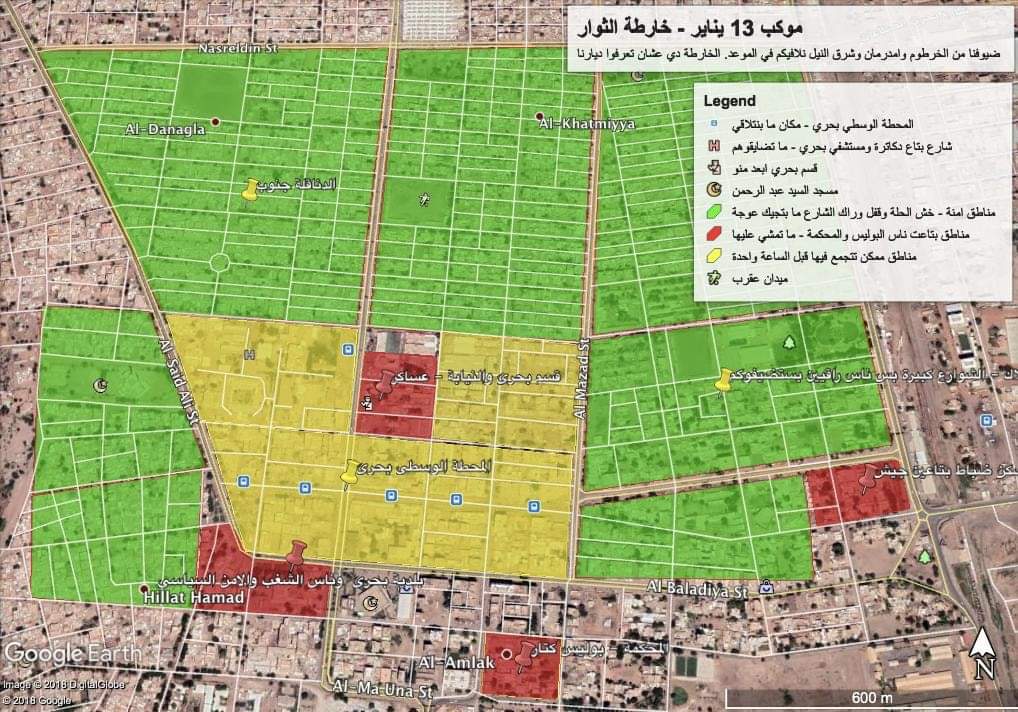

Each official SPA Facebook post bore a space, in the comments, for narratives from the public. By opening up the posts to public comments and including the public in the act of revision, the SPA plans were extended to include new areas for demonstrations (such as local neighborhoods) and undermined if they were impractical or dangerous. After posts were published on Facebook, the SPA had their people monitoring and taking in stories and layered responses that spawned from the platform as a result. People knew their locality and could immediately recognize that the producers of these plans in the SPA were not aware of, or local to, the area they were visualizing. Taking into account this local knowledge, the SPA would re-publish altered versions of plans in a matter of hours on social media. These two strands of collective thinking and instantaneous strategizing have given an imagining of a revised urbanscape of Khartoum’s public spaces predicated on urgencies determined by people’s direct engagement with the public space. The social media platform—though a globally contested space in relation to resistance movements—reconstituted the threshold of ‘public’ and ‘space’. In political discourse, ‘public space’ has always been a component of the state rhetorics of ‘democracy’. However, it has mostly been used to justify less than democratic policies: the creation of exclusionary urban spaces; state coercion and censorship; surveillance; economic privatization; the repression of differences; and attacks on the rights of the most expendable members of society, on the rights of strangers, and on the very idea of rights.

The publication of the plans on Facebook transformed the SPA’s propositions as the social media platform allowed for people to add on their suggestions and interact with the plans as if they were their own production—integrating live commentaries, drawings, live broadcasts, music pieces, and chants. These different strands pushed for a political spatial analysis that challenged the SPA’s assumptions about where demonstrations should and could take place in the city, moving into local areas and small neighborhoods. The commentary culminated in a collective effort to imagine existing together outside of state terror. This temporality has morphed social media platforms into a charrette—an intensive planning session where citizens, designers and others collaborate on a vision for development. In the digital space, the SPA gathered around the plans along with the people (and the state overlooking everything) and were able to reflect the people’s aspirations for justice.

Bahri is a town extending from Khartoum on the other side of the River Nile, and the ‘Bahri plans’ serve as a good example of the revisions of plans by the public. A part of the revised plan shows arrows pointing upwards, accompanied by a text, addressing the demonstrators, stating “Move forward and peace be with you” and “Secure yourself or retreat!”. Another side of the plan states “Go towards Almazad” (a neighbourhood in Khartoum) and showed scattered spaces surrounded by state police forces and security buildings, forming an enclosure. The areas marked in red were where the demonstrators would face the terror of live ammunition, tear gas, and the fate of indefinite incarceration and torture. Everyone wanted to be together on the other side, indicated in green, on the maps—moving forward and walking towards Almazad. It was as if from inside our homes, the neighbourhoods, the street, we’d be outside state terror, outside the injustice. The revised urban plan on social media provided an example of a reading of the city that was based on an urgency defined by the people to congregate and connect in their needs and aspirations for a better future.

Imagine what the built environment would look like should space making include all the layeredness of people’s knowledge of their environment, their aspirations for the future, and their revolutionary narrative. A clear spatial conversation had been carved out between people, the SPA, and the state—thus an entire ecology of engagement with the public space was mediated through the digital platform. Two narratives were generated from the spatial conversation: one being engendered through social media by protestors reacting to the SPA posts, and another through the transformations the SPA plans underwent. In the act of transforming both what was on the ground and on Facebook, both spaces gradually fused—the public space of the streets and the public space that was introduced by social media.

The events and demonstrations in Khartoum displayed how deficient our spatial literacy is in connection to what people want to become. Our future should always be a collective spatial production that incorporates people’s present lives, so that ‘becoming’ is distinguishable from merely existing in preconceived notions of space. We should push a line of inquiry into space in relation to such political events of resistance to state terror, as an opportunity to bring architecture to bear what is happening in the public spaces, both digital and physical, of Khartoum.

✨This is the seventh essay in a series of seven commissioned essays for 2019. With these original essays, our aim is to publish work that engages with digital visual culture, both in its niche manifestations and within the technological, political, and mainstream reality of the internet. Want to be the first to know when our next essay is published, stay up to date on our activities, or just find the latest ‘must sees’ on the internet? You can have all that and more when you sign up for our newsletter!